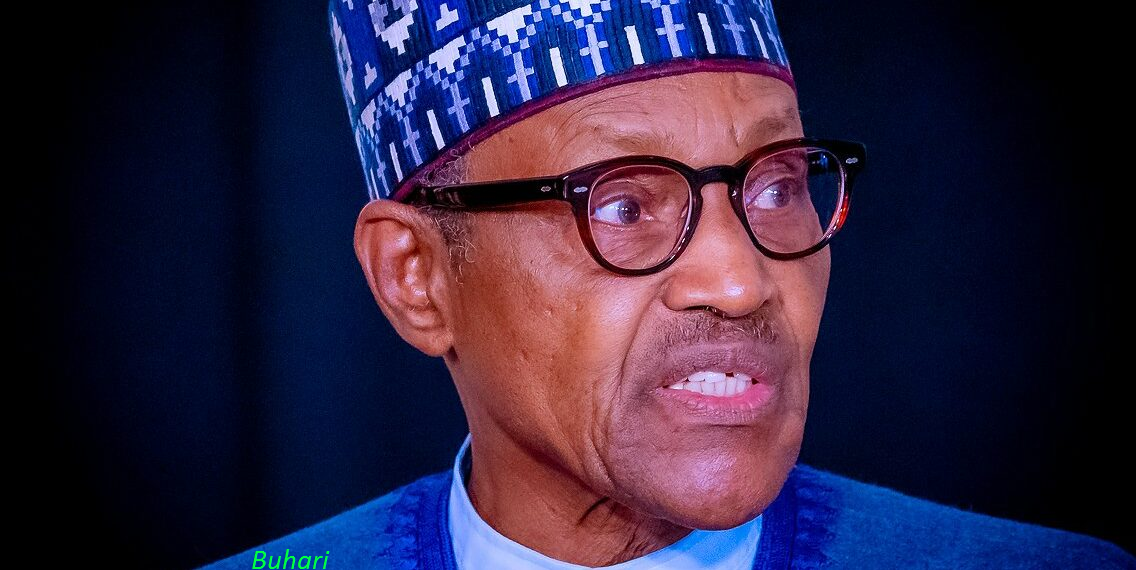

The death of former President Muhammadu Buhari GCFR, at 82 years, in a London hospital, following illness, is a huge loss to members of his family and to Nigeria as a whole. This country lost a leader whose years of service and contribution to nation-building would long be remembered for their impact on individual lives and the corporate existence of the country. This much is expected from him, having served as military Head of State of Nigeria for about 18 months, and later civilian president for eight years. To many people, Buhari has joined the league of heroes past who made undeniable sacrifices to keep Nigeria together – a patriot indeed. To many others still, Buhari’s sacrifices for Nigeria’s unity and his ambition to make Nigeria a great country were not enough to harness the country’s massive diversity and achieve that enviable potential. But there is little doubt that Buhari gave his all.

Born in Daura, Katsina State, in 1942, Buhari attended Katsina Provincial Secondary School. He joined the Nigerian Military Training College in 1962, and got advanced military training in the United Kingdom, India and the United States. His military training was put to test during the Nigerian Civil War (1967-1970), when he fought alongside federal forces to restore peace and order in the country. Like the others, Buhari endured both emotional and physical scars of that war until his passing. He never failed to profess his commitment to a strong, united Nigeria.

As a Lieutenant Colonel in 1975, Buhari was among the officers who brought General Murtala Muhammed into office in a military coup. He was later appointed military governor of the then North-eastern state, now comprising six states. Those who knew him then testified to his dedication to duty and zero tolerance for corruption. He also served as Federal Commissioner for Petroleum Resources and served as pioneer Chairman of the Nigerian National Petroleum Corporation (NNPC), from 1976 to 1978. He is credited with reforms in the oil and gas sector, including initiating the construction of 5,120 kilometres of the pipeline linking 23 storage depots, eight liquefied petroleum gas stations, 24 pump stations, two refineries and two offshore jetties.

Buhari became prominent after the coup of December 31, 1983, that ousted the second republic civilian government of President Shehu Shagari. Fellow putschists declared Buhari Head of State and Chairman of the Supreme Military Council. The 1979 Constitution was suspended, and the country went through one of its toughest military dictatorships. Buhari’s agenda was to revamp social order and stamp out corruption in the public space, using the mantra War Against Indiscipline, and in the process, curtailing civic rights to a level of public disenchantment.

The State Security (Detention of Persons) Decree 2 of 1984 was enacted, granting his government the power to detain individuals considered to constitute security risks to the state, without charge for up to three months. Many citizens became victims of the law, including Fela Anikulapo Kuti. Tunde Thomson and Nduka Irabor, journalists with The Guardian Newspaper, were also jailed under the Public Officers (Protection Against false Accusation) Decree 4 of 1984, a draconian law that forbade publication or transmission of any statement that could ridicule or discredit the government or public officers.

Thus, Buhari and his Chief of Staff, Supreme Headquarters, the late Brigadier Tunde Idiagbon, ran a no-nonsense regime during which media and civic rights were undermined. That was when Buhari earned the reputation of a principled and unyielding military officer among his colleagues and Nigerians. The excesses and rigidity of that regime, however, provided the excuse for the bloodless palace coup of August 1985, when Gen. Ibrahim Babangida replaced Buhari and relaxed the stranglehold on the civic space.

Out in the cold for the three years he was detained, Buhari kept a low profile, hardly seen in public and never made public statements on national issues. He was later made to serve in the Petroleum Trust Fund (PTF) created by Gen. Sani Abacha to manage funds derived from petrol subsidy from 1995-1999. Under his watch, PTF recorded a fair public rating in the establishment and maintenance of public infrastructure, particularly roads. But the Abacha government was economical with transparency and accountability issues.

Eventually, Buhari decided to take a shot at civilian governance in 2003. Some of his stalwarts were to claim much later that though he disliked politicians for their obvious crooked style, he was persuaded to get involved to checkmate the growing menace of the militia group, Oodua Peoples’ Congress (OPC) in Kwara State. Before then, he confronted former Governor Lam Adesina of Oyo State in 2000, over violent clashes between farmers and herders in Oke Ogun, in his (Buhari’s) capacity as grand patron of the Miyetti Allah Cattle Breeders Association.

Muslim groups and transition of Buhari, Awujale

After that encounter, Buhari’s image of a patriot and nationalist began to whittle. He became a member of the All Nigeria Peoples Party (ANPP), on which platform he sought to become president twice in 2003 and 2007. Each time, his efforts yielded 12 million plus votes, not enough to make the presidency. He didn’t give up, as he formed his own party, the Congress for Progressive Change (CPC) in 2011, and again ran for election and failed. The coalition of opposition parties in 2014 birthed the All Progressives Congress (APC), on which Buhari finally realised the ambition to once again lead Nigeria.

Buhari’s second coming was remarkable. He was marketed as a civilianised democrat as against his former military despotic rigidity, and as having zero tolerance for corruption. On military experience, Buhari was touted to be the solution the country needed to conquer the Boko Haram insurgents that had troubled the North-East since 2009. Against the backdrop of the Goodluck Jonathan administration’s lacklustre performance, the coalition had a smooth ride, and Buhari was inaugurated into office on May 29, 2015.

However, Buhari failed to hit the ground running. It took him months to constitute the Federal Executive Council, and he spent months in hospitals abroad. When he formed the cabinet, the composition was heavily criticised for lacking a nationalistic touch of federal character. Instead, Buhari began to exemplify crass insularity and parochialism, as he justified the selection of a kitchen cabinet made of people he could trust. His other appointments largely rewarded party loyalists and reflected where the votes came from. His famous statement that “constituencies that gave me 97 per cent cannot in all honesty be treated equally, on some issues, with constituencies that gave me five per cent” was highly instructive of his actions.

The economy under Buhari underperformed. By 2016, the economy officially entered a recession, recording a significant decline in activity and negative growth in the first and second quarters. The GDP contracted by -0.36 per cent and -2.06 per cent, respectively. That sluggish performance persisted until Buhari left office in 2023. It led to hardship for citizens, with increased unemployment, inflation and a decline in living standards. The Buhari government, through the Ways and Means lifeline in the Central Bank (CBN), left a debt of more than N20 trillion. Despite his advertised aversion to corruption, the menace thrived under his administration.

On insecurity, Buhari initially leveraged on his military experience to collaborate with neighbouring countries to counter Boko Haram insurgency. But his efforts buckled, and soon, insurgency mutated into terrorism, banditry, kidnapping and other crimes. When terrorists killed more than 40 worshippers at St Francis Catholic Church in Owo, Ondo State, on June 5, 2022, Buhari neither visited the crime scene nor showed any appreciable concern.

The best he did on the frequent killings by herdsmen of communities in Benue and Plateau States was to make statements sympathetic to the nomadic nature of terrorist herdsmen, urging communities to accept them as their kinsmen. He thereby gave credence to the theory that his government enabled diaspora Fulanis to invade the country to grab land.

In all, Buhari seemingly meant well for Nigeria, but his vision was narrow and incapable of galvanising the country or harnessing its diversity. Despite staking his poor health for Nigeria, he left the country in a more deplorable state than he met it. His approximate nine years in charge of Nigeria should send signals to the current and aspiring leaders that Nigeria is a complex entity, best governed through the formation of pragmatic federalism, and not through mere personal determination and inordinate ambition.

The Guardian