- A piece of Silver in the Smithy’s forge

By Yinka Fabowale

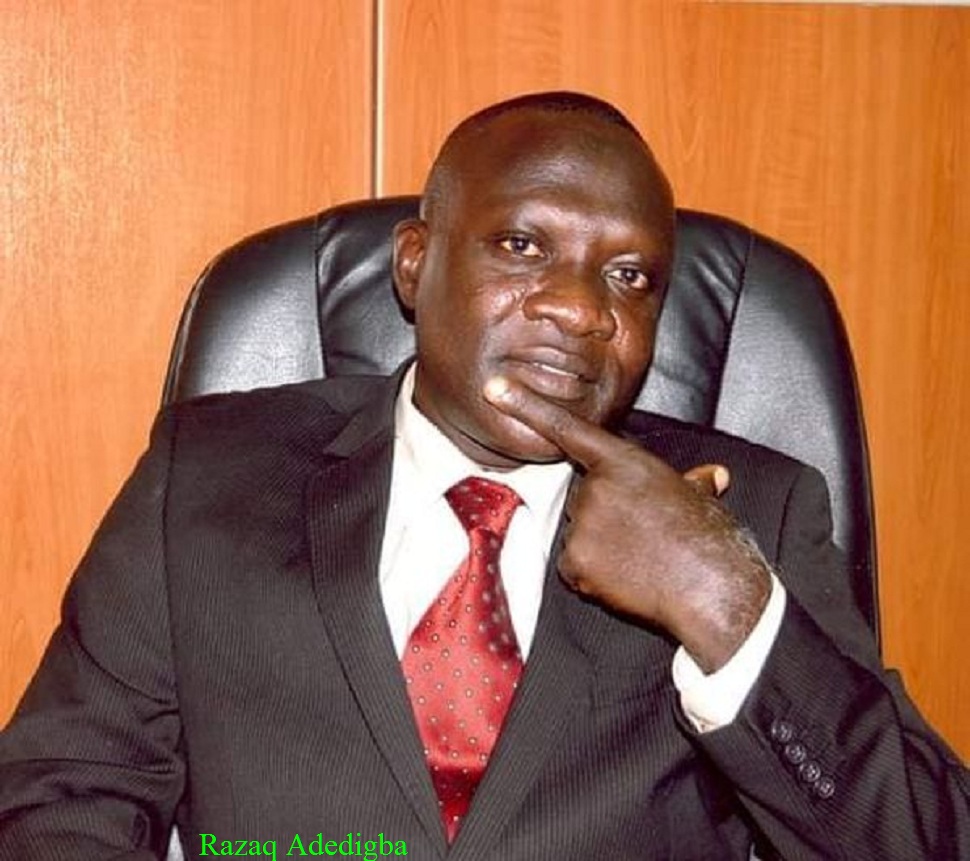

At last, a path to escape this prison of numbness and shame was shown, and from the most unlikely of places! Of all my ‘traducers’, there was none I probably feared more than Mr. Razaq Adedigba, the Chief Sub Editor. I really wouldn’t know which I dreaded more – his growls when he reprimanded or a mocking grin he had reserved for Newsroom drones like me when he sighted one on the company’s premises. I avoided him as much as I could.

I was returning from the upper floor of the building where I’d gone for a matter I cannot now remember when I saw the ‘menace’ appear on the corridor. As usual he broke into his derisive grin and as we drew level, sneered: “What (story) have you for us today?”He preempted my reply with an almost accurate guess: “Nothing as usual, abi!”, he jeered, the wicked grin widening, while his angry eyes lashed at me, taking contemptuous sweeps from my head to toe. Just as they did when on another occasion, he’d crumpled and thrown into the trash bin a news story I’d hoped would earn me a berth on the newspaper cover.

Based on an official memo from the office of the Head of Service, Lagos State, Adedigba had killed the report on the ground that it lacked depth, failed to exhaust the diverse perspectives and interviews with all the stakeholders.

I’d thenceforth followed the Chief Sub’s advice to treat documents as mere raw material out of which a bigger story could be generated. It paid off when I applied this principle to a state government policy paper which rolled out new procedures and adjustment of fees in the sand digging industry. I visited sand diggers in various beaches and spent time talking to other people in the construction industry, estate agents and valuers and allied fields.

The incredible harvest of information afforded insight into the wide spectrum of the issue that enabled me turn in a comprehensive report on the subject. Although I was disappointed when I did not see the story either on the front or back cover of the newspaper the next morning, I felt gratified to find it published as the lead report of the Property and Environment pull-out the following Monday.

Gradually, my stories started to feature prominently, sometimes as lead on the front page of the first edition, but ending up on page 3 or failing to make the second edition at all. I felt grateful to Adedigba for his constant needling and saw him as one whose brain I needed to pick to succeed on the job.

So, on this fateful encounter I pinned him down on his remark: “Mr. Man, o o l’idea! (Man, the trouble is you’re bereft of story ideas!).” “I accept, Oga. I have no idea,” I said and went on to confide in him how I had been hampered by my restricted background experience, lack of a beat and insufficient source base. Adedigba’s mien softened as he offered a few tips. One of these was for me to start following up on reported stories.

I’d obviously been too harassed by the barrage of malicious scorn and overwhelmed by the pressure of expectations by the editors that I’d forgotten this simple method of sourcing news taught in basic reporting class! Reactions and follow-ups on breaking stories often made bigger news! Adedigba’s hint liberated my mind and restored my self-confidence. I proceeded to befriend the library.

The Guardian library revealed the gross disadvantage in working in a startup media house such as the fledgling Lagos Horizon where I came from which had no library. There I busied myself with studying the nation’s dailies, magazines and other sources searching for stories with potential for further exploration.

More and more, my presence in the newspaper became felt, especially after I was detailed to cover the 1991/92 Federal Government- Academic Staff Union of Universities (ASUU) industrial dispute which resulted in a prolonged work boycott by the university teachers. My bosses were impressed, while I won the confidence of ASUU’s top hierarchy, which, seeing The Guardian’s sympathetic reportage and support for the campaign for revamping the ivory towers and education sector in general, became more willing to volunteer privileged information.

However, I owed much of the credits of my perceived accomplishments at that time to the healthy competition offered by Laolu Akande who also had links with credible sources at the ASUU headquarters at the University of Ibadan, and also regularly filed stories from the Oyo State capital that either corroborated my findings and facts or furnished fresh insights into changing trends in the protracted face-off.

On the final day, just as I finished submitting a report on a press conference addressed by ASUU, accepting government’s terms and calling off the strike, my ‘old’ boss, Mrs. Lawrence accosted me asking that I write a Focus story with the benefit of my experience in reporting the saga. I pleaded with her to give me till the following day, seeing that it was late and I was heading home to try and sleep off accumulated fatigue of the past weeks.

I knew my will, like my size, could not match Mrs. Lawrence’s. But from the wings I saw Esu wink an assurance. He was on my side and I wasn’t to fret, he whispered. Looking and feeling like I would drop dead any moment, I saw Mrs. Lawrence contemplate my condition with motherly compassion.

Glad, I made to pour libation in gratitude and homage to him who straddled the spot at which the three footpaths met, but alas, the vagabond- trickster went to incite the ‘spirit’ of Olukoso, whose habitation, I’d long suspected, with all the bawling and yelling, hollering and bellowing, the frothing from steaming intellectual pots, heat waves from the furnace of creative smiths, the surging and effervescing of energies in this space, was here or certainly nearby!

I saw the granite return to the Features Editor’s face. “It’s for the next edition of the Focus page, Yinka, it must come out before this thing goes out of the news,” she pressed.

I let out a heavy sigh…Again, a flicker of doubt, a wavering in Lawrence’s eyes, as Elegbara, in a confounding mind game of yo-yo, played the spritely Osun against the visceral god with dreadful visage emitting deadly currents of energy yearning to be pressed into action. Although intense, the inner conflict was sharp and short. The American would not submit to a silly hypnotic spell by some African deity. Abruptly, she turned her back and ordered that I follow her.

To Adedigba’s court she marched me for the matter to be decided. Even before the verdict was pronounced I knew I would not get a fair trial or justice. And just as I suspected, I had to stay overnight in the office to serve my sentence. But I begrudged neither the judge for his unjust judgment nor Pilate for her vain act of ablution. I reckoned it was all part of the code for training and toughening an aspiring member of The Guardian SEAL.

After the story was published, Adedigba called and commended me for what he described as my impressive handling of the writing, despite being under pressure.But, the creepy ghosts wouldn’t entirely go away.

A day or so after ASUU called off its strike, I ran into a colleague on the premises who praised my coverage of the ASUU crisis, but he betrayed his insincerity when he suddenly burst into laughter and asked mischievously: “So, after ASUU, what next?”Of course, I got the message. He obviously saw my performance on the task as a fluke.

The test of a reporter’s competence was not in latching on to a running story, but in independent assertions and exertions.

To be continued.