- He who would dance with the gods

By Yinka Fabowale

The call

A 1986 graduate of Communication and Language Arts from University of Ibadan with a postgraduate diploma of the Nigeria Institute of Journalism (NIJ), Ogba, Lagos, I had worked as an Information Officer at the Lagos State Ministry of Information and Culture since 1987, courtesy of an automatic employment the then state governor, Mike Akhigbe granted me and 24 other youth corps members for winning the National Youth Service Corps (NYSC) Merit Award out of more than 2,000 graduates who participated in the scheme in the 1986/87 service year.

But a dull routine of pushing files in the civil service with its red tape was certainly not in my career dream which was either to become a journalist, (preferably broadcast) or artiste/entertainer. I also mulled the idea of going back for postgraduate studies for which I’d already been offered admission in preparation to becoming a teacher in my old department at UI. But, I couldn’t take up the admission offer because of the state government’s gesture.

My deployment along with five senior colleagues in the ministry as pioneer editorial staff of the newly established state newspaper with senior editors hired from Daily Times of Nigeria marked the beginning of my romance with and immersion into “active journalism”. The Lagos Horizon job was an exciting and learning experience, as my new bosses from DTN, also of the finest professional breed, apparently recognizing my enthusiasm and potential, threw virtually everything at me and me at virtually everything – proofreading, rewriting, leader writing, column writing, arts/literary review, news feature writing, in addition to reporting the Governor’s Office/State secretariat, Alausa.

These professionals who helped in honing my budding talents and skills were: the late Mr. Tunde Odesanya, a former Deputy Editor of Daily Times and Chairman, Nigeria Union of Journalists (NUJ); Soga Odubona, Assistant Editor, Sunday Times; Segun Ojo, Chief Sub Editor; Muyiwa Owolabi, Production Editor and ‘Aunty’ Agbeke Ogunsanwo, a former Editor of Headlines, who had Earlier been appointed and was retained in the ministry as Director of Information.

By 1990 I was already considered one of the “star writers” on the weekly newspaper by readers, colleagues and my bosses including no less a personality than the Editor himself.

Then began the incitement to go for the broke, leave the pool and go fish in the mighty ocean of the Nigerian media. With fresh spiritual insight and orientation, I agreed one should seek a broader platform to further nurture and deploy one’s God-given abilities for greater social impact.

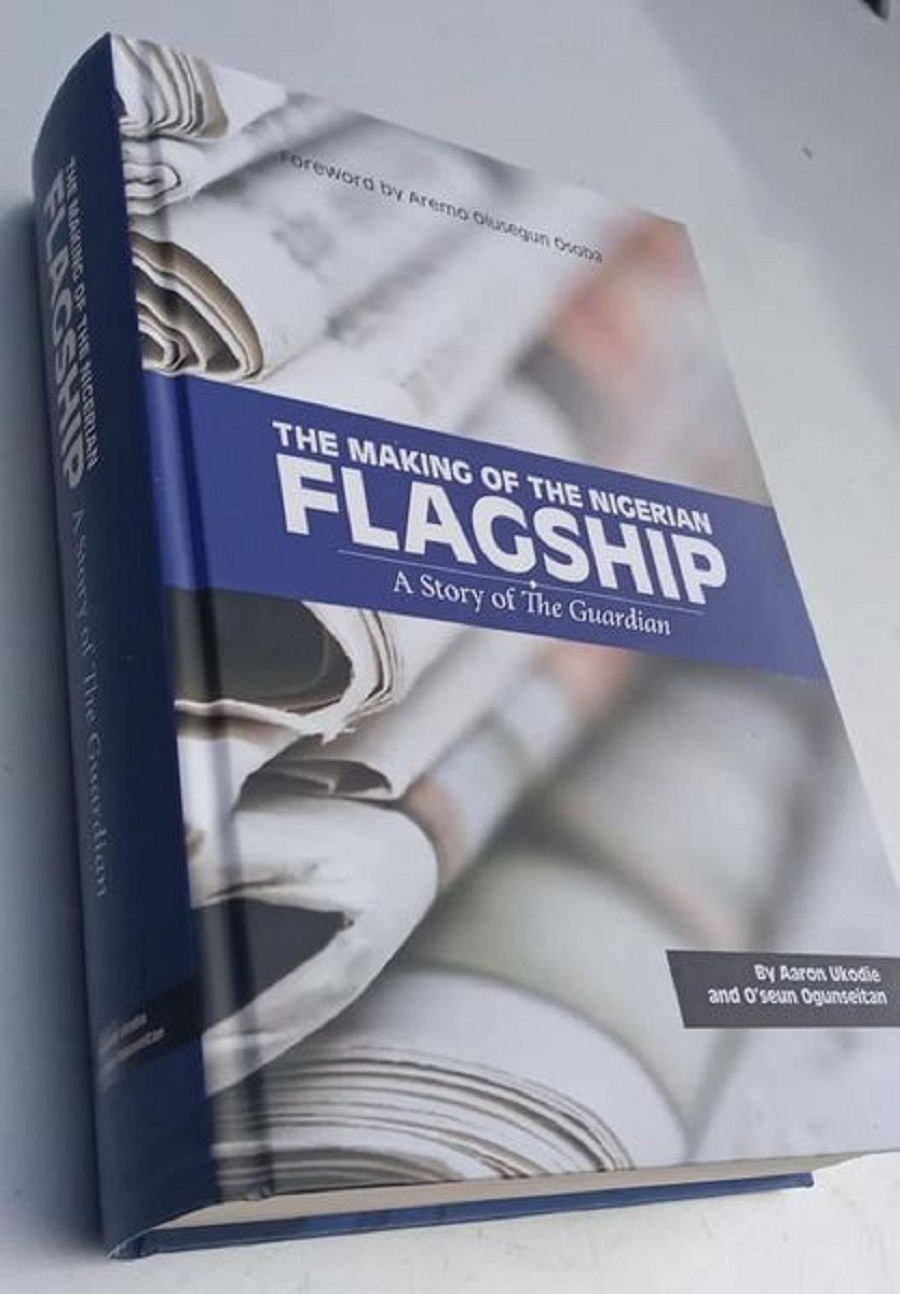

The pull to The Guardian was natural. The newspaper’s hallmarks of excellence, service, intellectualism, sober temperament, and philosophy of justice, truth and path-finding captured in its motto: “Conscience nurtured by the truth” as well as the inimitable logo, a lamp, held more than fascination, they were ideals on which I was nurtured and was committed to.

What more, I had been impressed by the brilliance, mien, comportment among other qualities shown by members of The Guardian family I’d encountered outside the walls of the reputable news medium, either as colleagues/acquaintances or as participants at some public fora I attended. Among these were Jahman Anikulapo, Akin Ogunrinde, Bayo Oguntimehin (Bros B), Taiwo Akinyemi and Gboyega Adejumo.

Bros B, of course, had established a reputation for himself as the Dean, nay, Don of we, correspondents at the seat of government, Alausa. While other reporters chatted and idled away at the Press Centre of the Governor’s Office, only covering functions involving the state helmsman or his commissioners, Bros B was busy scouting for scoops in the ministries, publication of which frequently embarrassed us, his colleagues.

While still in the ministry, his visits to our office guaranteed drama between him and the Head of my unit, a lady, who would get jittery and start clearing her table of official memos, circulars, etc, once The Guardian reporter came in grinning. Regarding him suspiciously, my boss would ask the newsman: “Ehen, Bayo, what is your big cat sniffing this time? What are you looking for in my office?”

The Guardian reporter’s standard reply was to ask in mock offence: “What is there to sniff or steal in your office? Is this not a press room? Is it an offence to come see my colleagues?” Yet as he spoke, his eyes would rove. Sometimes he picked up a brief on the table and appear to read it, sending the officer, caught off-guard, to scream and struggle to retrieve the document presumably containing classified information!

But we knew Oguntimehin was merely fooling. The Information Ministry was not where he got the ‘exclusives’ and other vital information that distinguished his reports from ours. He came around only to confirm routine information.

Also, I’d been shocked when at the end of a public lecture I attended somewhere in a housing estate in Iyana Ipaja area in 1990, while in search of the meaning of life and existence, one of the hosts identified the guest speaker as the Managing Director of The Guardian, Mr. Lade Bonuola (Ladbone). The simple albeit neatly dressed and soft-spoken dark-skinned gentleman with a face scarred by Yoruba tribal marks didn’t fit the image of Ladbone, who, although I’d not met before then, I’d concluded could not be other than an Englishman or British -born Nigerian, what with his European-sounding nickname (Pseudonym) and legendary mastery of the English grammar and journalistic literary rules I’d been familiar with since his DTN days!

The simplicity, humility, and passion the media icon exuded in the discharge of that task coupled with child-like glow in his eyes and a perceptible warmth in his gentle, but hearty laughter played no small part in my evaluation of and ultimate disposition to the subject of his address on that fateful day.

Similar impression assailed me when I was introduced to Mr. Kusa about a year later when I felt the urge to hearken to my own inner stirring and urgings by friends to move to The Guardian.

How great it would be to walk the same grounds and breath the same air in the proximity of intellectual and literary giants who were making waves with their fecund, critical and creative faculties – Prof. Femi Osofisan, Dr. Edwin Madunagu, Prof. Onwucheka Jemie, Prof. Olatunji Dare, Prof Godwin Sogolo, Andy Akporogu, Ike Okechukwu, Ambassador Dapo Fafowora, Ted Iwere, Prof. Dipo Otubanjo, Dr. G.G. Darah, Al-Bishak, Abd-Rafiu, Uthman Shodipe and many others who offered the Nigerian reading public compelling, critical multi-disciplinary, multi-perspectival dissection and exposition on issues in the public space; with a rainbow of engaging literary styles ranging from the simple, lucid and dramatic to woven tapestries of poetry, logic and cryptic thoughts, suffused, in some cases, with Marxist-leftist ideological lingo and terminologies, but holding for the reader who braved the challenge of intellectual exertion to crack the message the reward of an epiphany in the very reading experience itself.

All this casts The Guardian as the 20th Century version of King Arthur Richard’s legendary court, the famous Noble Knights of the Roundtable, admission into which demanded utmost proof of not just courage, chivalry and good swordsmanship (in metaphorical sense), but also integrity and wisdom.

“Lesi ma woju Ekun lai s’awo? (“Who dares poke the tiger in the eye, but a brave?).Convinced that the conditions were not too much a price to ask by the media institution which, like its English sibling of the crusade era was a public trust fighting a war to secure the realm against new forms of enemies, to Kusa I raced… panting, to heed the bugle!

To be continued