By Lola Fabowale

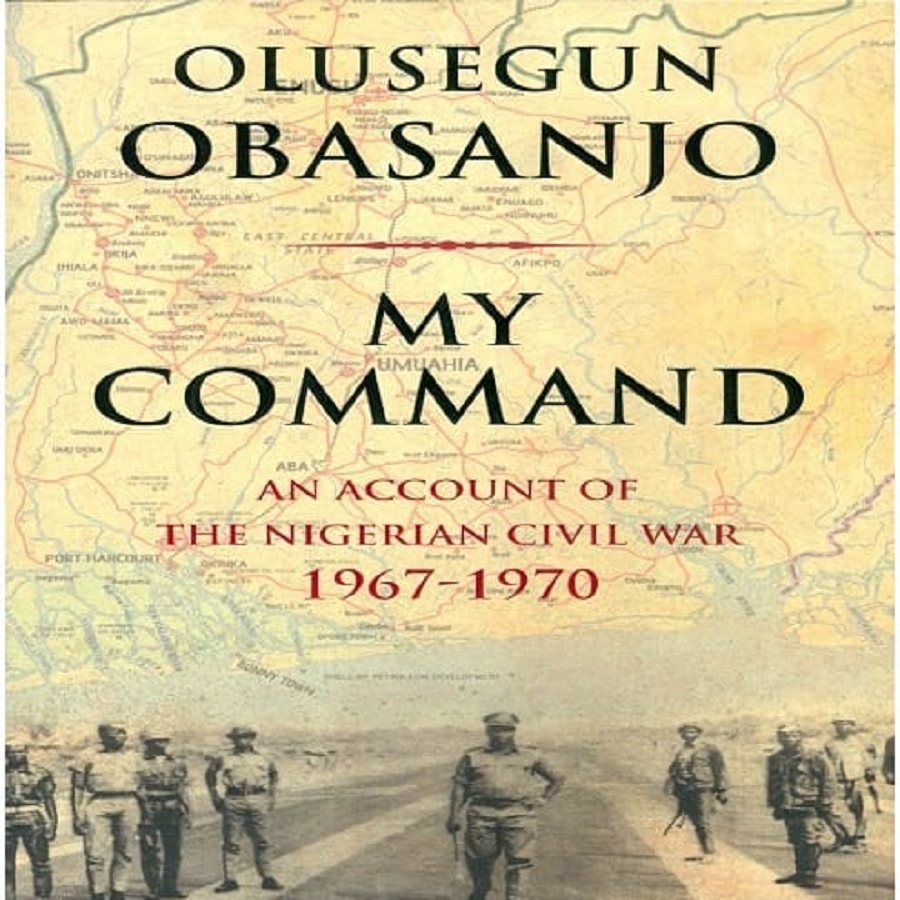

“Men are still the most important instrument in the art of war [be that spiritual, emotional, psychological or physical]. Without them other machines, equipment and instruments of war are useless, no matter how sophisticated”.—Olusegun Obasanjo In My Command: An Account of The Nigerian Civil War 1967-1970: p. 97.

Introduction

Save for the odd editing glitch, My Command, an account of the Nigerian-Biafran war by a federal war prosecutor—General Olusegun Obasanjo–provides a holistic view of the antecedents, motivations, processes, implications and enduring lessons of the 1967-1970 war.

This review of a book on that war which ended more than 50 years ago might seem outdated were the current feudalistic apparitions rearing their ugly heads again in the country not prime candidates for the book’s instructions.

Obasanjo’s book tells a cautionary tale that should guide Nigeria’s current leaders against callous brinkmanship as seen in incendiary comments about “speaking to them [i.e Southern secessionists] in the only language [of violence] that they can understand”.

Particularly telling in this regard is a poignant lament which should proffer apt warning and incentive for current federal and regional actors to seek early pathways to lasting peace: “What seems to me to be a human tragedy all through the ages is the inability of man to learn a good lesson from the past so as to avoid the pitfalls of those who had gone before …As a result, history tends to repeat itself. But there are exceptions of nations and men who had learnt from history to avoid collective and individual disasters or are exceptions of such disasters”.—-p. 249.

Nigeria’s current leaders should take heed and eschew a 1967 mindset that believes that international opinion would be favourable and unchanging for a unitary as opposed to a federalist or even secessionist cause.

The case for open minds

Before reading the book from cover to cover, I had been privy only to the commentary of its critics/detractors about it being a thinly shrouded attempt by the General to blow his own horn of supposedly shallow military accomplishments while disloyally thrashing admirable nationalistic figures such as late Major Chukwuma Kaduna Nzeogwu who was his close friend but whom fate had temporarily cast aside into political dis-favour for perceptions that the January 1966 coup he had masterminded was ethnically motivated against Northerners. My own observations bends more towards a positive assessment of the author’s work.

Granted, the twice former head of state—once in military and later in civilian garb—does light up his laurels in the book by sharing how he shored up the morale of the 3 Commando Division of which he was Commander after both sides had reached a stalemate to contribute towards the federalist ultimate victory. Still he has done students of Nigeria’s history, politics and military strategy an invaluable service by providing a rather balanced account of the war from a federalist perspective.

Nuggets of surprise

The book recognizes enduring cleavages among Nigerian ethnic groups and Britain’s avaricious post-colonial designs as fodders for the war. Far from demonizing Nzeogwu, it hails him as a charismatic and fully “detribalized” Nigerian who wanted to serve the nationalist cause but for diverse reasons found himself on the Biafran side on which he died–ambushed.

The book is less charitable towards Late Lieutenant Colonel Chukwuemeka Odumegwu-Ojukwu–the Biafran leader whose “power-hungry” tactics unduly prolonged the war even though the Centre fired the first shot. Nonetheless, future editions of the book might better highlight rather than downplay how the pogrom of the Igbo living in the North following the July 1966 revenge coup by Northern military officers fanned the embers motivating the Biafran cause.

Aside from such shortcomings, the book provides an insightful account of ethnic infiltration of the Centre’s structures and processes that variously prolonged but ultimately truncated the war in favour of the federalists. It is instructive that despite the preponderance of federal manpower, creative home-engineered weapons of war by the so-called Biafran rebels such as ‘red devils’ and “Ogbunigwe” resulted in a stalemate that could have yielded a Biafran victory were it not for Ojukwu’s incursions into the Western and Mid-West regions which tilted their residents’ sentiments to favour the federalist cause.

Such lessons should not be lost on President Muhammadu Buhari’s current unitary bent, despite nearly unanimous calls for a truly decentralized federal structure where power is effectively shared among all levels of government rather than monopolized by the Centre.

General Obasanjo acquits himself for not selling out on the federal military institution when supposedly asked to “name his price”. His demeanor in this regard sheds some light on his tumultous relations with the unnamed but recognizable “social critic and author” who wanted him to side with those who might have steered the country onto a better and glorious course than the war path on which she currently seems headed again.

Considerations

With the benefit of hindsight of how badly the country had fared since the war, one wonders, borrowing the author’s own favourite quote from Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar if his principled stance was not a rebuff of “…a tide in the affairs of [Nigeria] which, taken at the flood, leads on to fortune; omitted, all the voyage of …life is bound in shallows and in miseries”.

Still, can one spurn such a General for remaining loyal to the most national institution in the country then even though he himself recognized how porous the same institution had been to ethnic-based sentiments? Had he relented, might not the war been protracted?

Conclusion

In ‘My Command,’ Obasanjo has given Buhari enough to chew on how he should sit up–read the lessons of history of the Nigerian-Biafran war well so that with well-meaning regional leaders, he might promote a more equitable, “detribalized Nigeria” that would lift the tide of fortune again and acquit him as a true modern patriotic leader rather than a feudalistic and tribalistic warlord.