By Olusola Adeyegbr

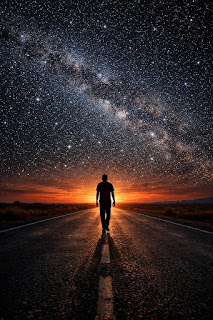

Human life is framed by a certainty we often push to the edges of our thinking: it will end. Death is not an interruption to life’s story. It is the boundary that gives the story its shape, earnestness, and meaning. We live on a rock spinning through space at astonishing speed, in a universe so vast that our planet is barely a speck among trillions of galaxies. Yet, in the middle of all this, we spend our days worrying about opinions, small failures, social comparisons, and imagined embarrassments.

It is a sobering thought. If we knew with certainty that tonight would be our last night on earth, how would we spend this day? Would we still be anxious about the meeting we stumbled through, the comment someone made, or the risk of trying something new? Or would our attention shift instantly to the people we love, the words we have not said, and the dreams we have postponed?

This is where the popular advice comes in: live each day as if it were your last. At first glance, it sounds liberating. It invites courage. It cuts through fear. It pushes us to act, to forgive, to start, to speak, and to love without hesitation. Many people have found strength in this idea. It reminds us that time is not guaranteed, and that procrastination is often just fear wearing a polite face.

But taken literally, this philosophy can also be misleading.

If every day were truly our last, long-term thinking would lose its meaning. We would not bother saving money, building institutions, raising children, or planting trees whose shade we might never sit under. Civilizations are built on the assumption that tomorrow matters. Laws, schools, research, infrastructure, and families all depend on a i8future-oriented mindset.

There is also a risk of confusing urgency with recklessness. Some people interpret the “last day” idea as permission to abandon discipline, indulge every impulse, or ignore responsibilities. That is not wisdom. It is short-termism disguised as courage.

So perhaps the idea is not meant to be taken literally, but morally.

The deeper lesson is about focus. If death is certain, then the real question becomes: what deserves our attention while we are here? Many of the things that dominate our thoughts will not matter at the end of our lives. The fear of embarrassment, the anxiety of comparison, the small grudges, the hesitation to try. These are often the chains that keep people from living meaningfully.

Thinking about mortality does not have to lead to panic. It can lead to clarity. It can help us distinguish between what is urgent and what is important, between what is noisy and what is meaningful.

A balanced approach might be this: live in such a way that if today were your last, you would not feel ashamed of how you spent it. But also live in such a way that if you wake up tomorrow, you are grateful for the seeds you planted today.

This means holding two truths at the same time. Life is fragile, and the future is uncertain. Yet life is also long enough to require planning, discipline, and patience. Wisdom lies in honoring both realities.

So instead of asking, “What would I do if this were my last day?” a better question might be, “What kind of life would make any day, even the last one, feel complete?”

That question shifts the focus from drama to character, from impulse to purpose. It encourages us to love people well, do our work with integrity, pursue our callings, and release the trivial anxieties that consume so much of our mental space.

Yes, we are on a small rock spinning through a vast universe. Yes, our time here is limited. But that is not a reason to live carelessly. It is a reason to live deliberately.

When we accept our mortality, fear loses some of its power. Opinions matter less. Failure becomes less frightening. What remains is the discipline of living a life that counts, measured not in noise or acclaim, but in integrity and consequence.