This left governments with the additional burden of sourcing additional resources to survive.

Understandably, the pandemic holds an opportunity for telecommunication operators who have been saddled with the responsibility of bringing physically distant relations, colleagues and associates to virtual interaction, leading to a geometric rise in the demand for data.

For instance, Nigeria’s telecommunications’ exceptional performance lifted the country out of recession in the fourth quarter of 2020, after it contributed 12.45 per cent to the country’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP). Telecommunications and information services, which have benefited positively from the lockdown and restricted movement that started last year, grew by 17.64 per cent in Q4 2020, over seven percentage rise from 10.26 per cent it recorded in Q4 2019.

While telecommunications industry posted huge profits from the increase in the social relevance of their businesses, the banks recorded losses. Data from the United Kingdom, for instance, suggest that a total of 4.4 million payment deferrals had been sealed from the start of the pandemic and last October. Extending into this year, banks in the UK, Europe and other regions are providing respite to borrowers who are too burdened with heightened financial challenges to honour debt obligations.

Recently, the European Central Bank (ECB) warned that the industry would not see profitability return to the pre-pandemic era till 2022. The frontline battle is how banks can cover operational expenses to be able to support businesses as the global economy seeks to weather the resurging COVID-19 storm.

“The total gross loans of these banks rose from N3.9 trillion in 2010 to N13.6 trillion in 2020 or by 248 per cent. The positive outliers for growth are Access Bank (growing quickly even before its 2019 merger with Diamond Bank), UBA and Zenith Bank,” the report said.

According to 2020 financial statements analysed, the total assets of the top five bank groups – Access, First Bank of Nigeria, Guaranty Trust Bank, United Bank for Africa and Zenith – rose to N37.5 trillion last year, from the pre-pandemic value of N29 trillion, which translates to about 25 per cent growth year-on-year.

Speaking at a seminar organised by the Finance Correspondents Association of Nigeria (FICAN), last week, Yusuf said much of banks’ assets are channeled to treasury bills, while financial intermediation – the core responsibility of banks – is abandoned. He said the banks must focus on their core mandate to support economic growth.

Last year, Zenith Bank’s treasury bill portfolio increased by close to 60 per cent (from N991 billion to N1.58 trillion), its loans and advances grew by merely 20.5 per cent to N2.78 trillion.

Access Bank also grew its loan portfolio by over 70 per cent in the past three years, a feat partly attributed to its merger with the defunct Diamond Bank, with the figure hitting N3.6 trillion as of December 31, 2020. Yet, securities and other assets weigh heavily on its book.

Besides, a larger proportion of banks’ total credit is extended to the exclusive public and oil/gas while sectors that have direct impacts on the people were left in limbo. Of the N20.4 trillion total industry credits as of December 31, 2020, the government had N1.8 trillion. The amount was about 18 per cent increase from the N1.5 trillion reported at the close of 2019.

The combined Profit After Tax (PAT) of the five players analysed, which are classified as systemic important banks, also rose from N684 billion in 2019 to N719.7 billion. On average, the five banks’ portability grew by five per cent in the same year most of their physical operations were shut down to contain the spread of COVID-19.

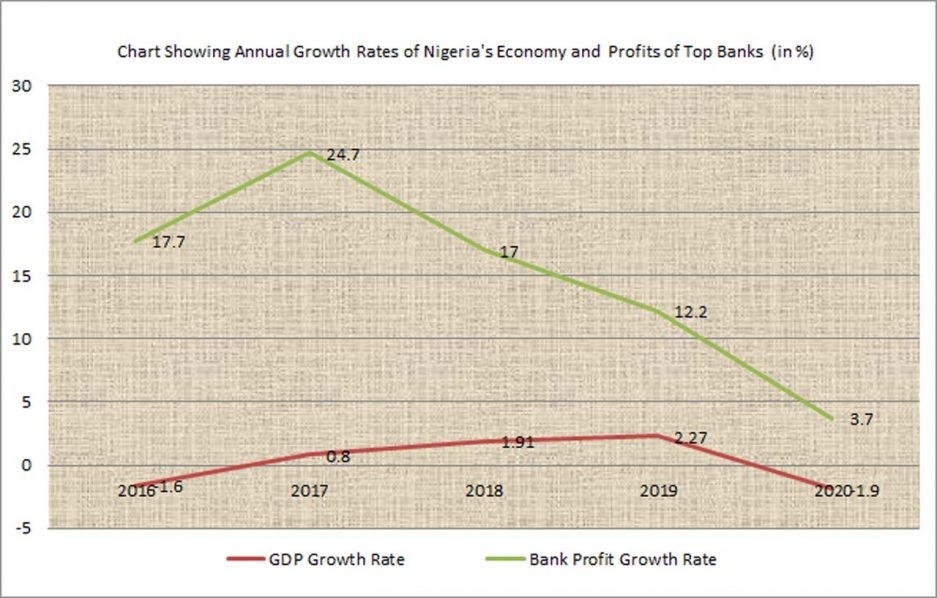

From 2016 to 2020, the top five banks made a total PAT of N3.3 trillion, with a year-on-year profit growth of between 3.7 and 24.7 per cent. Sadly, the economy they service dipped into recession twice in the same period. Two out of the five years, the GDP wobbled through negative growths.

Perhaps, Nigerians would bother less if there were no perception that banks make huge profits off the sweat of the poor masses. After a protracted battle between the telecoms and banks, the cost of Unstructured Supplementary Service Data (USSD) pegged at N6.98 per transaction has been passed to depositors.

Despite warning that the charge would threaten financial inclusion, the fee has been passed on as one of the numerous fees banks impose on depositors. For Nigerians, the USSD is another burden too many to bear for patronising the financial system. The World Bank said the cost of banking was a major reason behind the high global unbanked population, 3.4 per cent of who are Nigerians.

Certainly, technology has made banking services more comfortable for millions of Nigerians but it does not make it any way cheaper. Time has changed, so also is the true worth of a bank account holder.

A customer is charged for every transfer, after which she is notified that she has been debited N26 service fee or whatever amount applicable depending on the value of transactions. Then, she is notified of both the transfer and the fees in separate messages, both of which attract N4 SMS charges.

And if the poorly-serviced Automated Teller Machines (ATMs) scrape off the card’s security chip and render it invalid, one is debited N1, 000 to replace it. In all of these, there are associated SMS and VAT charges.

When Dele transfers N10, 000 to Chukwu via his mobile app, the former is charged a transfer fee plus value-added tax (VAT). Then, Chukwu is credited N9, 950 as N50 stamp duty is withheld by the bank for the remittance to the Federal Government. On both ends, SMS notifications –account plug-in services by default – are sent and the fees are debited against the two accounts involved.

To widen the banking net, agency banking was conceived in 2017. Now, agency ‘bankers’ are also gradually assuming the status of a vampire, sucking dry the traditional cash dispensing channels of banks, even in the cities.

Sadly, banks seem to have channeled more resources to the agency model, while pulling back on ATM service, leaving those who need cash with no choice but to visit the roadside kiosks where cash is more readily (albeit in piecemeal) but charges higher.

Charges linked to digital and other offline transactions are numerous and growing. And to encourage more depositors to embrace modern banking tricks, there is a penalty for cash above a certain threshold. This keeps more people going online and increasing the volume of transaction fees.

The Guardian