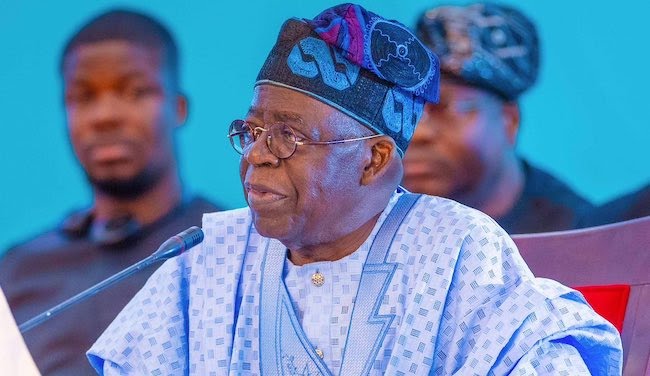

President Bola Tinubu

The Federal Government is right to have, on September 28, 2025, pushed back against narratives seeking to pitch Nigeria’s fight against terrorism in religious storylines. Such narratives are too simplistic to be allowed to distort the insurgency and terrorism that have afflicted the country for about one and a half decades. The truth is that Nigeria’s insecurity crisis is multifaceted and grows primarily because the government has failed over the years to provide for the security and welfare of the people, a basic responsibility entrusted to it by the Constitution.

Government inertia or grossly inadequate response steadily emboldened a so-called “ragtag” insurgent into the now sophisticated army of criminals bold enough to regularly confront the Nigerian security forces right in their territories. The solution to these distractive narratives lies not merely in their denial but in the government’s concerted drive to rein in terrorism permanently.

Minister of Information and National Orientation Mohammed Idris described such claims as “false, baseless, and dangerously divisive.” Barely a week later, Senior Special Assistant to the President on Digital Engagement and Strategy, O’tega Ogra, was on the same trail, affirming, “Nigeria will not be lectured by those who confuse our struggle for security with a struggle of faith. Our constitution forbids any state religion, and for centuries, Muslims and Christians have coexisted side by side.”

Nothing could have been further from the truth. The country must not risk a fatal plunge over the precipice with sectarian narratives. Terrorism prowls in diverse garbs, speaks many dialects and exploits several local grievances. Like Justitia, the authorities must emplace the blindfold of impartiality and wield the sword against all perpetrators, regardless of their nameplates.

That many Christians and leaders of the faith have been targeted, kidnapped, killed, and their churches destroyed is a well-documented fact. Research by the Catholic Secretariat of Nigeria (CSN) is said to have detailed 145 kidnappings of priests and the killing of 11 between 2015 and 2025. A 2025 report by a faith-based organisation even claimed that the lives of some 32 Christians are cut short in the country every day, while over 7,000 followers were murdered nationwide in the first 220 days of 2025. The pains of the June 2022 Owo massacre, in which about 50 worshippers were killed, remain fresh in many minds.

These incidents are now being described in charged terms such as “cleansing” or a “clergy abduction spree.” Once framed this way, they feed conspiracy theories that portray the violence as an organised attempt to wipe out one group on religious grounds. Such narratives, once internalised, distort public perception and cause many to interpret government actions solely through this divisive lens.

Over the years, however, mosques have also been attacked, imams killed, and Muslim congregations terrorised. On August 19, 2025, gunmen raided a mosque in Katsina State during morning prayers, killing about 50 worshippers, with dozens more burned to death in nearby villages. Attacks on mosques have been reported in previous years as well. In a 2020 incident, five worshippers were murdered and more kidnapped in a Zamfara mosque; the imam was among those seized.

More recently, on September 15, 2025, bandits struck again in the state, repeating the same pattern with the abduction of dozens of worshippers. Also, in June 2024, about a dozen armed men on motorcycles attacked Tudun Doki in Sokoto State’s Gwadabawa District early Sunday morning, just hours before Eid al-Adha prayers, killing six and kidnapping nearly 100 people.

The implication is that the onslaught on innocent citizens across the country is a crisis larger than any single creed. It is a bloody mix of insurgency, banditry, herders-farmers clashes, ransom economies, and communal conflicts. Boko Haram and Islamic State West Africa Province have committed mass atrocities for more than a decade, displacing millions in the North-East. Armed gangs have preyed on villages, abducted for ransom, torched farms, and seized land in the North-West and parts of the Middle Belt. Parts of the North-West and South-West have also seen rising activity by armed attackers. On September 28, 2025, about 12 people were killed in Kwara State as armed bandits struck Oke-Ode town. Clearly, it is civilians, rather than any particular faith, who suffer.

India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi captured the context aptly in a May 2015 interview with TIME magazine, when he declared: “We should not look at terrorism from the nameplates: which group they belong to, what is their geographical location, who are the victims? These individual groups or names will continue to change. We need to delink terrorism from religion, to isolate terrorists who use this interchange of arguments between terrorism and religion. We should see it as something that is a fight for human values.”

The Federal Government must go beyond merely debunking allegations of sectarian undertones in Nigeria’s security crisis and eliminate anything that could give rise to such claims. The country, with over 200 million citizens, lies along very sensitive ethno-religious fault lines and appears to have survived six decades of tense moments largely by providence rather than by consistent, deliberate leadership. Through actions or inactions, prompt or delayed responses, utterances, or even ‘body language’, authorities must never allow their conduct to be interpreted as favouring any section of the country over another.

The Federal Government’s focus on countering inflammatory claims about terrorism is welcome. It is an essential step towards ensuring the current security crisis does not escalate into a serious existential threat, and that bad actors do not exploit such claims to pursue destructive agendas. Progress made in the fight against terrorism, such as the arrest of the Ansaru sect leaders, should be sustained. There must also be a renewed commitment to the impartial enforcement of the Terrorism Prevention and Prohibition Act 2022. All who dare to test its provisions must also experience its capacity not only to bark but to bite.

Granted that the war against terrorism is far from being conventional, the war, nevertheless, must not be allowed to drag on endlessly, else it attracts all sorts of complexities and narratives that distort the actual dimension of the crisis. After about 16 years of insurgency and trillions of naira budgeted and spent on the war, the federal government, along with its military and other law enforcement agencies, cannot escape blame for making the war a permanent feature and industry. This is the time to rethink and restrategise with the sole aim of ending insurgency. It is obvious that the security agencies, with their single command structure, are overwhelmed.

Why is it taking an eternity for the government to decentralise the agencies into a state structure, for better effect? For how long will state police continue to thrive on paper rather than in practice? When will governors be empowered to take full charge of their domains instead of praying for federal presence while their people are hacked to death daily? What cause have the leaders to celebrate anything or even be happy, when the life of the average Nigerian has become meaningless and valueless; when mass murder and arson no longer provoke any real concern of the elite, or when trading of human beings in the guise of ransom has become the order of the day? Or when millions of Nigerians have become refugees and internally displaced right in their homeland? Government, at both federal and state levels, must sit up and set a timeline to end terrorism and other criminality, so that Nigerians can breathe, and the country can shed its stigma of being among the worst places to live in globally.

There is no smoke without fire. When rumours or insinuations persist, they may be hints at deeper problems or uncomfortable truths beneath the surface. It is both embarrassing and troubling that a government in a constitutional democracy must repeatedly deny claims that rising insecurity and mass killings follow an ethno-religious pattern. Such perceptions may linger unless Nigeria confronts fundamental questions about its very foundation: What, exactly, did its peoples agree to when they became one nation? Was that union freely negotiated or imposed? Honest answers to these questions are essential if divisive narratives are to be disarmed and trust in the state restored.

The Guardian